What is vacuuming?

Every time we update a row in Postgres, it adds a new version of the row and marks the old version as invalid. Also postgres doesn’t physically remove a deleted row from the disk, instead, it marks it as invalid. These rows continue to stay in the database until a vacuum is done. So vacuuming is just reclaiming this space occupied by dead rows and making it available for re-use.

Why does Postgres maintain versions of its rows rather than changing the actual value on disk?

This is primarily done to support MVCC(multi-version concurrency control). MVCC primarily is an optimization technique to prevent excessive blocking when reading or writing a piece of data, i.e. multiple transactions can access the same data concurrently without locking the data. It allows Postgres to implement different levels of isolations when running transactions that are concurrently working on the same data. This implies that during the process of querying a database, every transaction is presented with a snapshot of data (referred to as a database version) from a specific moment in the past, irrespective of the current state of the underlying data. This safeguard ensures that the transaction does not encounter inconsistent data resulting from concurrent updates made by other transactions to the same data rows. Thus, it guarantees transaction isolation for each database session.

Witness Every Update Unfold as New Versions:

We can witness that every time we update a row, a new one is created. We can get the “CTID” field of a row, which denotes the physical location of the data, and we can check if it changes for every update.

CREATE TABLE NAMES(

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

first_name text,

last_name text);

-- creating an example table called names

insert into names(first_name,last_name) values (‘hello’,’world’);

insert into names(first_name,last_name) values (‘hye’,’there’);

insert into names(first_name,last_name) values (‘sup’,’’);

-- inserting sample values to the names table

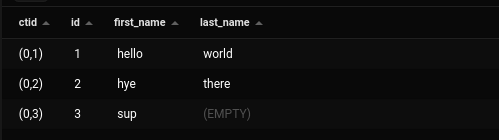

select ctid,* from names

This will create a table with three rows and display the ctid and data of all the rows we have inserted in the table

This picture shows us the ctid of each row, the first number in ctid shows us the page number and the second number represents the tuple number. This represents the location where the disk stores the row.

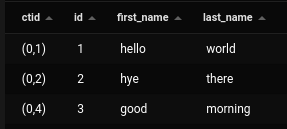

If we update our row we will notice that the ctid of our row will change, which tells us that instead of updating the row on the disk where it is located, Postgres has created a new version of the row and has marked the other one as invalid.

update names set first_name=’good’,last_name=’morning’ where id = 3;

If our table is not vacuumed, it will get bloated and slow down sequential table scans. It becomes extremely necessary to vacuum our database regularly to minimize disk space usage.

By default, Postgres SQL automatically vacuums the table when 20% of the rows plus 50 rows are inserted, updated, or deleted. This setting is good enough for smaller databases, but in the case of larger databases, it makes much more sense to tweak these settings.

Vacuum/ auto-vacuum will not return disk space to the O.S.(unless in case the most recent pages are made empty), but instead the database will become emptier, and future updates/inserts will use the recovered space.

If you want Postgres to return disk space to the O.S. you should use vacuum full, but it takes much longer and exclusively locks the table. This method also requires extra disk space, since it writes a new copy of the table and doesn’t release the old copy until the operation is complete. Usually, you should only use this method when you need to reclaim a significant amount of space from within the table. This can cause significant downtime and is not recommended for high-workload systems.

Checking if the vacuum recovers the dead tuples and reuses them for future updates and inserts:

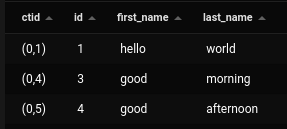

We are going to use our earlier names table. First, we will delete a row and add a new one, then we will check if it will reuse the ctid or not.

delete from names where id = 2;

insert into names(first_name,last_name) values (‘good’,’afternoon’);

As we can see we get a new ctid for the newly inserted row.

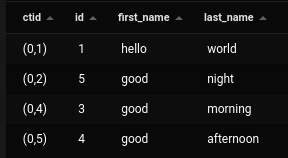

Now we will vacuum our table and again insert a new row into our table

vacuum;

insert into names(first_name,last_name) values (‘good’,’night’);

As we can see, Postgres has reused the same CTID (same disk location), and vacuuming was successful.

Best practices for vacuuming:

- Auto vacuum can use significant resources in your database, so you should try to schedule it during periods of low traffic.

- You should always fine-tune your auto vacuum settings.

- Vacuuming is just one aspect of database maintenance. To keep your database running smoothly, it is essential to incorporate other maintenance tasks such as index maintenance, database backups, and routine system health checks.